Pierre Rousseaux is a PhD candidate in economics at CREST, Institut Polytechnique de Paris (France).

As part of his PhD, his research focuses on labor economics, econometrics, and policy evaluation. Specifically, he studies the job search behavior of job seekers, informational frictions in the hiring process, and the effects and design of unemployment insurance. Additionally, his research also pertains to international trade, using product-level trade and production data to study vulnerabilities within global value chains and their evolution in response to various risks. He is also the director, co-founder, and editor in chied of Oeconomicus, an online journal that promotes the results of economic research, makes it accessible to public debate, and brings together actors of the academic community to enhance the understanding of research in economics as well as their own research.

Strengthening the European Union’s economic resilience: How to address trade dependencies?

Supply chain disruptions from the pandemic, the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and economic pressures from China have pushed economic security to the forefront of the EU’s agenda. These sudden and large-scale shocks required swift action from European Union (EU) member states. The challenge now is for the EU to proactively anticipate and mitigate trade risks while maintaining the benefits of traditional gains, the key element being to accurately identify trade vulnerabilities. In the third chapter (Mejean and Rousseaux, 2024) of the CEPR-Bruegel Paris Report 2, together with Isabelle Mejean we develop a methodology that identifies EU product-level trade dependencies, isolate them according to their risks, and discuss policies that could mitigate these vulnerabilities.

Hyper-globalization of Global Value Chains (GVCs): Enhanced efficiency at the expense of lower resilience?

GVCs are intricate networks coordinating production across various stages from inception to consumer purchase, involving multiple buyers and suppliers. Over the past three decades, GVCs have hyper-globalized, leading to geographically dispersed production. This fragmentation has increased trade gains and provided risk-sharing against country-specific shocks (Backus et al., 1992; Antràs and Chor, 2021). However, it has also concentrated production in specific nodes, heightening the exposure of countries and firms to local supply shocks. With production dominated by a few actors, disruptions in one node can ripple downstream (di Giovanni et al., 2020; Bonadio et al., 2021; Boehm et al., 2019).

These concentrated dependencies, known as “global trade dependencies,” have spurred policy and academic debates, particularly during crises like the Covid-19 pandemic, which revealed high reliance on a few countries for critical goods, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which highlighted the risk of trade weaponization. The rise of trade dependencies and resilience policies creates a trade-off between traditional trade benefits and increased resilience. Policymakers have made addressing these dependencies a priority, seeking to balance economic interdependence with strategic autonomy and supply chain resilience. Indeed, the U.S. and the EU have implemented resilience policies, such as the 2021 Executive Order on America’s Supply Chains and the European Chips Act, through import diversification and local production.

Governments must act proactively, as firms often underinvest in resilience due to network and information externalities (Mejean and Rousseaux, 2024). Resilience investments by firms typically benefit others, leading to underinvestment (Grossman et al., 2021). Additionally, firms may be unaware of indirect risks from their suppliers, a non-marginal issue in the EU (Mejean and Rousseaux, 2024). The primary challenge for resilience policies is to accurately identify vulnerabilities and isolate them according to specific risks.

Diagnosing EU trade vulnerabilities: Methodologies and results

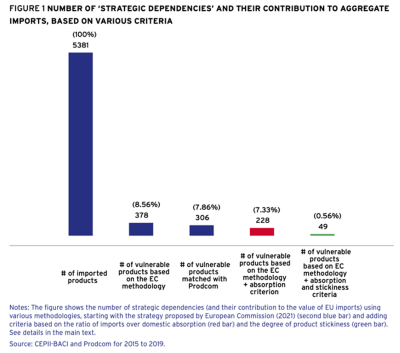

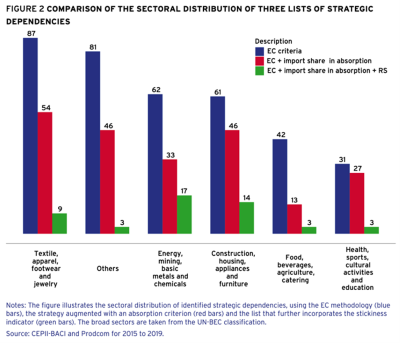

Several methodologies have emerged following the Covid-19 pandemic, including those by the French Treasury (Bonneau and Nakaa, 2020), the French Council of Economic Advisors (Jaravel and Mejean, 2021), the European Commission (2021), Mejean and Rousseaux (2024), and the CESifo (Baur and Flach, 2022) [1]. The European Commission (EC) methodology identifies a product as vulnerable if it simultaneously meets criteria for import concentration, the significance of extra-EU imports, and the substitutability of these imports with domestic exports. Using product-level trade (CEPII-BACI) and production data (Eurostat-PRODCOM), we add in our paper to these criteria the potential for domestic and post-shock substitution, focusing on products mainly reliant on extra-EU imports to meet domestic demand (absorption) and with very low supplier substitution potential [2]. These factors play a crucial role for resilience (Moll et al., 2023), and recent trade literature using natural experiments has provided empirical evidence of post-shock substitution patterns (Lafrogne-Joussier et al., 2023). Incorporating these substitution patterns in vulnerability analysis refines dependencies and changes their sectoral distribution.

From Mejean and Rousseaux (2024)

Figure 1 sequentially shows how our additional criteria impact the set of vulnerabilities imported by the EU. Beginning with 5,381 products imported by the consolidated EU from 2015 to 2019 (we aggregate trade and production data to focus on persistent dependencies), the European Commission’s three criteria identify 378 vulnerable products. Restricting the set to products for which 50% of domestic absorption is satisfied by extra-EU imports reduces it to 228 products. Finally, by considering ex-post substitutability in the event of a shock affecting these products, we identify 49 strategic dependencies after narrowing down to those (among the 228) with very low substitutability between suppliers. This last set of vulnerabilities accounts for 0.5% of the EU’s total imports. These products are notably concentrated within the energy, mining, basic metals, and chemicals sectors (Figure 2). Additionally, most of these strategic dependencies are associated with products primarily sourced from China. This final set includes for instance alkaloids, quebracho extract, trichloroethylene, raw beryllium, and bismuth. All identified products and their uses are available in the original paper.

[1] A review and discussion of the others are available in Mejean and Rousseaux (2024) and in Vicard and Wibaux (2024).

[2] A detailed and technical description of these methodologies is provided in the main text and Appendix A1 in Mejean and Rousseaux (2024).

From Mejean and Rousseaux (2024)

Intersecting vulnerabilities with risks: A normative approach

Existing data is crucial for identifying potential trade vulnerabilities, though not all vulnerabilities pose equal risks to the economy. Several arguments support interventions to enhance resilience. In the paper, we have analyzed the identified vulnerable products through four key risk lenses. All selected products and their use can be found in the original paper.

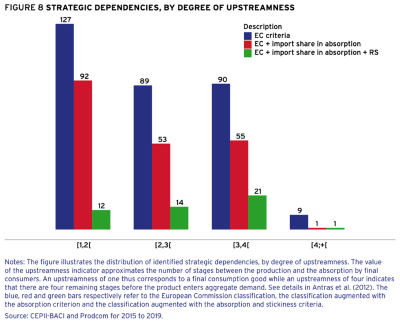

First, we examined geopolitically risky products by identifying 41 products sourced from non-NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) countries, four of which are sourced from countries with high geopolitical risk. Resilience policies should also consider the estimated economic cost of disruptions, along with the product’s importance in the value chain. To pursue this argument, we have linked vulnerable products to their position within GVCs and identified 22 products that increase EU supply chain risks (Figure 8).

From Mejean and Rousseaux (2024)

Beyond economic costs, disruptions in critical goods, such as pharmaceuticals, can lead to severe non-economic consequences, including human losses. EU trade dependencies in pharmaceuticals are however limited due to significant European production and flexibility in sourcing active ingredients. We also highlighted a selection of green products (cobalt, lithium, rare earth metals, and graphite) and renewable technologies (lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, solar panels, and hydrogen). While not currently identified as vulnerable by our methodology, these products are likely to become so if the EU fails to secure essential inputs. This risk is amplified by the concentration of these resources among a few non-EU suppliers and their low potential for substitution.

Public policies to mitigate trade vulnerabilities

After identifying trade vulnerabilities and isolating products based on the specific risks that resilience policies aim to address, different strategies can be employed to mitigate these vulnerabilities. Various risks and vulnerabilities require tailored approaches. Increase supplier (and technology) diversification, particularly towards geopolitically stable countries, and increase domestic production to reduce reliance on non-EU sources are two key policies. Subsidies that support domestic production, especially in sectors highly dependent on foreign inputs, can enhance overall risk diversification and strengthen the EU’s position within global value chains. This approach is particularly compelling for green industries.

However, coordinating these subsidies, which fall under the purview of EU Member States, is crucial to prevent subsidy escalation and to correct imbalances between Member States. The allocation of public resilience investments should balance the need to reinforce existing industrial clusters with the goal of revitalizing regions that have suffered from declining manufacturing employment. Additionally, alternative strategies include investing in new technologies, public-private collaboration, standardizing production processes to enhance substitutability, and implementing real-time stock monitoring systems.

References

Antràs, Pol and Davin Chor, “Global Value Chains,” NBER Working Papers 28549, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc March 2021.

Backus, David K, Patrick J Kehoe, and Finn E Kydland, “International Real Business Cycles,” Journal of Political Economy, August 1992, 100 (4), 745–775.

Baur, A. and L. Flach, “German-Chinese Trade Relations: How Dependent is the German Economy on China?,” EconPol Policy Report 6, CESifo 2022.

Boehm, Christoph E., Aaron Flaaen, and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar, “Input Linkages and the Transmission of Shocks: Firm-Level Evidence from the 2011 T ̄ohoku Earthquake,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, March 2019, 101 (1), 60–75.

Bonadio, Barth ́el ́emy, Zhen Huo, Andrei A. Levchenko, and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar, “Global supply chains in the pandemic,” Journal of International Economics, 2021, 133 (C).

Bonneau, C. and M. Nakaa, “Vuln ́erabilit ́e des approvisionnements franc ̧ais et europ ́eens,” Tr ́esor-E ́co 274, French Treasury 2020.

di Giovanni, Julian, Andrei A. Levchenko, Isabelle. Mejean “Foreign Shocks as Granular Fluctuations,” NBER Working Papers 28123, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc November 2020.

European Commission, “Strategic dependencies and capacities,” Commission Staff Working Document, European Com- mission May 2021.

Grossman, Gene M., Elhanan Helpman, Alejandra Sabal, and Hugo Lhuillier, “Supply Chain Resilience: Should Policy Promote Diversification or Reshoring?,” NBER Working Papers 29330, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc October 2021.

Jaravel, Xavier and Isabelle Mejean, “A data-driven resilience strategy in a globalized world,” Notes du CAE, Conseil d’Analyse Economique April 2021.

Lafrogne-Joussier, Raphael, Julien Martin, and Isabelle Mejean, “Supply Shocks in Sup- ply Chains: Evidence from the Early Lockdown in China,” IMF Economic Review, March 2023, 71 (1), 170–215.

Mejean, I and P Rousseaux (2024), ‘Identifying European trade dependencies‘, in Pisani-Ferry, J, B Weder di Mauro and J Zettelmeyer (eds), Paris Report 2: Europe’s Economic Security, CEPR Press, Paris & London. https://cepr.org/publications/books-and-reports/paris-report-2-europes-economic-security

Moll, Benjamin, Moritz Schularick, and Georg Zachmann, “The power of substitution. The Great German Gas Debate in Retrospect,” Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 2023.